Monday, April 2, 2007

Women in Islam: Hijab

Ibrahim B. Syed, Ph. D.

President

Islamic Research Foundation International, Inc.

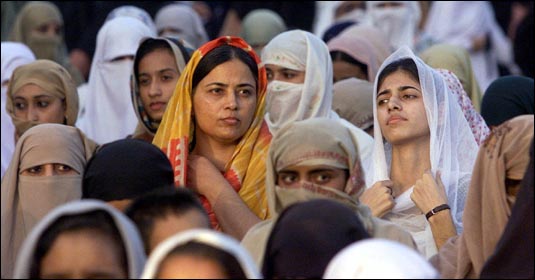

Literally, Hijab means "a veil", "curtain", "partition" or "separation. " In a meta- physical sense, Hijab means illusion or refers to the illusory aspect of creation. Another, and most popular and common meaning of Hijab today, is the veil in dressing for women. It refers to a certain standard of modest dress for women. "The usual definition of modest dress according to the legal systems does not actually require covering everything except the face and hands in public; this, at least, is the practice which originated in the Middle East." 1

While Hijab means "cover", "drape", or "partition"; the word KHIMAR means veil covering the head and the word LITHAM or NIQAB means veil covering lower face up to the eyes. The general term hijab in the present day world refers to the covering of the face by women. In the Indian sub-continent it is called purdah and in Iran it called chador for the tent like black cloak and veil worn by many women in Iran and other Middle Eastern countries. By socioeconomic necessity, the obligation to observe the hijab now often applies more to female "garments"(worn outside the house) than it does to the ancient paradigmatic feature of women's domestic "seclusion." In the contemporary normative Islamic language of Egypt and elsewhere, the hijab now denotes more a "way of dressing" than a "way of life," a (portable) "veil" rather than a fixed "domestic screen/seclusion. " In Egypt and America hijab presently denotes the basic head covering ("veil") worn by fundamentalist/ Islamist women as part of Islamic dress (zayy islami, or zayy shar'i); this hijab-headcovering conceals hair and neck of the wearer.

The Qur'an advises the wives of the Prophet (SAS) to go veiled (33: 59).

In Surah 24: 31(Ayah), the Qur'an advises women to cover their "adornments" from strangers outside the family. In the traditional and modern Arab societies women at home dress quite differently compared to what they wear in the streets. In this verse of the Qur'an, it refers to the institution of a new public modesty rather than veiling the face.

...When the pre-Islamic Arabs went to battle, Arab women seeing the men off to war would bare their breasts to encourage them to fight; or they would do so at the battle itself, as in the case of the Meccan women led by Hind at the Battle of Uhud. This changed with Islam, but the general use of the veil to cover the face did not appear until 'Abbasid times. Nor was it entirely unknown in Europe, for the veil permitted women the freedom of anonymity. None of the legal systems actually prescribe that women must wear a veil, although they do prescribe covering the body in public, up to the neck, the ankles, and below the elbow. In many Muslim societies, for example in traditional South East Asia, or in Bedouin lands a face veil for women is either rare or non-existent; paradoxically, modern fundamentalism is introducing it. In others, the veil may be used at one time and European dress another. While modesty is a religious prescription, the wearing of a veil is not a religious requirement of Islam, but a matter of cultural milieu.2

"The Middle Eastern norm for relationships between the sexes is by no means the only one possible for Islamic societies everywhere, nor is it appropriate for all cultures. It does not exhaust the possibilities allowed within the framework of the Qur'an and Sunnah, and is neither feasible nor desirable as a model for Europe or North America. European societies possess perfectly adequate models for marriage, the family, and relations between the sexes which are by no means out of harmony with the Qur'an and the Sunnah. This is borne out by the fact that within certain broad limits Islamic societies themselves differ enormously in this respect." 3

The Qur'an lays down the principle of the law of modesty. In Surah 24: An-Nur: 30 and 31, modesty is enjoined both upon Muslim men and Muslim women 4:

Say to the believing men that they Should lower their gaze and guard Their modesty: that will make for Greater purity for them: And God is Well-acquainted with all that they Do. And say to the believing women That they should lower their gaze And guard their modesty: and they Should not display beauty and Ornaments expect what (must Ordinarily) appear thereof; that They must draw their veils over Their bosoms and not display their Beauty except to their husbands, Their fathers, their husband's Fathers, their sons, their husband's Sons, or their women, or their Slaves whom their right hands Possess, or male servants free of Physical needs, or small children

Who have no sense of the shame of

Sex; and that they should not strike

Their feet in order to draw

Attention to their ornaments.

The following conclusions may be made on the basis of the above-cited verses5:

1. The Qur'anic injunctions enjoining the believers to lower their gaze and behave modestly applies to both Muslim men and women and not Muslim women alone.

2. Muslim women are enjoined to "draw their veils over their bosoms and not display their beauty" except in the presence of their husbands, other women, children, eunuchs and those men who are so closely related to them that they are not allowed to marry them. Although a self-conscious exhibition of one's "zeenat" (which means "that which appears to be beautiful" or "that which is used for embellishment or adornment") is forbidden, the Qur'an makes it clear that what a woman wears ordinarily is permissible. Another interpretation of this part of the passage is that if the display of "zeenat" is unintentional or accidental, it does not violate the law of modesty.

3. Although Muslim women may wear ornaments they should not walk in a manner intended to cause their ornaments to jingle and thus attract the attention of others.

The respected scholar, Muhammad Asad6, commenting on Qur'an 24:31 says " The noun khimar (of which khumur is plural) denotes the head-covering customarily used by Arabian women before and after the advent of Islam. According to most of the classical commentators, it was worn in pre-Islamic times more or less as an ornament and was let down loosely over the wearer's back; and since, in accordance with the fashion prevalent at the time, the upper part of a woman's tunic had a wide opening in the front, her breasts were left bare. Hence, the injunction to cover the bosom by means of a khimar (a term so familiar to the contemporaries of the

Prophet) does not necessarily relate to the use of a khimar as such but is, rather, meant to make it clear that a woman's breasts are not included in the concept of "what may decently be apparent" of her body and should not, therefore, be displayed.

The Qur'anic view of the ideal society is that the social and moral values have to be upheld by both Muslim men and women and there is justice for all, i.e. between man and man and between man and woman. The Qur'anic legislation regarding women is to protect them from inequities and vicious practices (such as female infanticide, unlimited polygamy or concubinage, etc.) which prevailed in the pre-Islamic Arabia. However the main purpose is to establish to equality of man and woman in the sight of God who created them both in like manner, from like substance, and gave to both the equal right to develop their own potentialities. To become a free, rational person is then the goal set for all human beings. Thus the Qur'an liberated the women from the indignity of being sex-objects into persons. In turn the Qur'an asks the women that they should behave with dignity and decorum befitting a secure,

Self-respecting and self-aware human being rather than an insecure female who felt that her survival depends on her ability to attract or cajole those men who were interested not in her personality but only in her sexuality.

One of the verses in the Qur'an protects a woman's fundamental rights. Aya 59 from Sura al-Ahzab reads:

O Prophet! Tell Thy wives And daughters, and the Believing women, that They should cast their Outer garments over Their Persons (when outside): That they should be known (As such) and not Molested.

Although this verse is directed in the first place to the Prophet's "wives and daughters", there is a reference also to "the believing women" hence it is generally understood by Muslim societies as applying to all Muslim women. According to the Qur'an the reason why Muslim women should wear an outer garment when go out of their houses is so that they may be recognized as "believing" Muslim women and differentiated from street-walkers for whom sexual harassment is an occupational hazard. The purpose of this verse was not to confine women to their houses but to make it safe for them to go about their daily business without attracting unwholesome attention. By wearing the outergarment a "believing" Muslim woman could be distinguished from the others. In societies where there is no danger of "believing" Muslim being

confused with the others or in which "the outer garment" is unable to function as a mark of identification for "believing" Muslim women, the mere wearing of "the outer garment" would not fulfill the true objective of the Qur'anic decree. For example that older Muslim women who are "past the prospect of marriage" are not required to wear "the outer garment". Surah 24: An-Nur, Aya 60 reads:

Such elderly women are Past the prospect of Marriage,-- There is no blame on them, if They lay aside Their (outer) Garments, provided they make Not wanton display of their Beauty; but it is best for them

To be modest: and Allah is One

Who sees and knows all things.

Women who on account of their advanced age are not likely to be regarded as sex-objects are allowed to discard "the outer garment" but there is no relaxation as far as the essential Qur'anic principle of modest behavior is concerned. Reflection on the above-cited verse shows that "the outer garment" is not required by the Qur'an as a necessary statement of modesty since it recognizes the possibility identification women may continue to be modest even when they have discarded "the outer garment."

The Qur'an itself does not suggest either that women should be veiled or they should be kept apart from the world of men. On the contrary, the Qur'an is insistent on the full participation of women in society and in the religious practices prescribed for men.

Nazira Zin al-Din stipulates that the morality of the self and the cleanness of the conscience are far better than the morality of the chador. No goodness is to be hoped from pretence, all goodness is in the essence of the self. Zin al-Din also argues that imposing the veil on women is the ultimate proof that men suspect their mothers, daughters, wives and sisters of being potential traitors to them. This means that men suspect 'the women closest and dearest to them.' How can society trust women with the most consequential job of bringing up children when it does not trust them with their faces and bodies? How can Muslim men meet rural and European women who are not veiled and treat them respectfully but not treat urban Muslim women in the same way? 7 She concludes this part of the book, al-Sufur Wa'l-hijab 8 by stating that it is not an Islamic duty on Muslim women to wear hijab. If Muslim legislators have decided that it is, their opinions are wrong. If hijab is based on women's lack of intellect or piety, can it be said that all men are more perfect in piety and intellect than all women? 9 The spirit of a nation and its civilization is a reflection of the spirit of the mother. How can any mother bring up distinguished children if she herself is deprived of her personal freedom? She concludes that in enforcing hijab, society becomes a prisoner of its customs and traditions rather than Islam.

There are two ayahs which are specifically addressed to the wives of the Prophet Muhammad (S) and not to other Muslim women.

These are ayahs 32 and 53 of Sura al-Ahzab. ".. And stay quietly in Your houses," did not mean confinement of the wives of the Prophet (S) or other Muslim women and make them inactive. Muslim women remained in mixed company with men until the late sixth century (A.H.) or eleventh century (CE). They received guests, held meetings and went to wars helping their brothers and husbands, defend their castles and bastions.10

Zin al-Din reviewed the interpretations of Aya 30 from Sura al-Nur and Aya 59 from sura al-Ahzab which were cited above by al-Khazin, al-Nafasi, Ibn Masud, Ibn Abbas and al-Tabari and found them full of contradictions. Yet, almost all interpreters agreed that women should not veil their faces and their hands and anyone who advocated that women should cover all their bodies including their faces could not face his argument on any religious text. If women were to be totally covered, there would have been no need for the ayahs addressed to Muslim men: 'Say to the believing men that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty.'(Sura al-Nur, Aya 30). She supports her views by referring to the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (S), always taking into account what the Prophet himself said 'I did not say a thing that is not in harmony with God's book.'11 God says: 'O consorts of the Prophet! ye are not like any of the(other) women' (Ahzab, 53). Thus it is very clear that God did not want women to measure themselves against the wives of the Prophet and wear hijab like them and there is no ambiguity whatsoever regarding this aya. Therefore, those who imitate the wives of the Prophet and wear hijab are disobeying God's will.12

In Islam ruh al-madaniyya (Islam: The Spirit of Civilization) Shaykh Mustafa Ghalayini reminds his readers that veiling pre-dated Islam and that Muslims learned from other peoples with whom they mixed. He adds that hijab as it is known today is prohibited by the Islamic shari'a. Any one who looks at hijab as it is worn by some women would find that it makes them more desirable than if they went out without hijab13. Zin al-Din points out that veiling was a custom of rich families as a symbol of status. She quotes Shaykh Abdul Qadir al-Maghribi who also saw in hijab an aristocratic habit to distinguish the women of rich and prestigious families from other women. She concludes that hijab as it is known today is prohibited by the Islamic shari'a.14

Shaykh Muhammad al-Ghazali in his book Sunna Between Fiqh and Hadith 15 declares that those who claim that women's reform is conditioned by wearing the veil are lying to God and his Prophet. He expresses the opinion that the contemptuous view of women has been passed on from the first jahiliya (the Pre-Islamic period) to the Islamic society. Al-Ghazali's argument is that Islam has made it compulsory on women not to cover their faces during haj and salat (prayer) the two important pillars of Islam. How then could Islam ask women to cover their faces at ordinary times?16 Al-Ghazali is a believer and is confident that all traditions that function to keep women ignorant and prevent them from functioning in public are the remnants of jahiliya and that following them is contrary to the spirit of Islam.

Al-Ghazali says that during the time of the Prophet women were equals at home, in the mosques and on the battlefield. Today true Islam is being destroyed in the name of Islam.

Another Muslim scholar, Abd al-Halim Abu Shiqa wrote a scholarly study of women in Islam entitled Tahrir al-mara'a fi 'asr al-risalah: (The Emancipation of Women during the Time of the Prophet)17 agrees with Zin al-Din and al-Ghazali about the discrepancy between the status of women during the time of the Prophet Muhammad and the status of women today. He says that Islamists have made up sayings which they attributed to the Prophet such as 'women are lacking both intellect and religion' and in many cases they brought sayings which are not reliable at all and promoted them among Muslims until they became part of the Islamic culture.

Like Zin al-Din and al-Ghazali, Abu Shiqa finds that in many countries very weak and unreliable sayings of the Prophet are invented to support customs and traditions which are then considered to be part of the shari'a. He argues that it is the Islamic duty of women to participate in public life and in spreading good (Sura Tauba, Aya 71). He also agrees with Zin al-Din and Ghazali that hijab was for the wives of the Prophet and that it was against Islam for women to imitate the wives of the Prophet. If women were to be totally covered, why did God ask both men and women to lower their gaze? (Sura al-Nur, Ayath 30-31).

The actual practice of veiling most likely came from areas captured in the initial spread of Islam such as Syria, Iraq, and Persia and was adopted by upper-class urban women. Village and rural women traditionally have not worn the veil, partly because it would be an encumbrance in their work. It is certainly true that segregation of women in the domestic sphere took place increasingly as the Islamic centuries unfolded, with some very unfortunate consequences. Some women are again putting on clothing that identifies them as Muslim women. This phenomenon, which began only a few years ago, has manifested itself in a number of countries.

It is part of the growing feeling on the part of Muslim men and women that they no longer wish to identify with the West, and that reaffirmation of their identity as Muslims requires the kind of visible sign that adoption of conservative clothing implies. For these women the issue is not that they have to dress conservatively but that they choose to. In Iran Imam Khomeini first insisted that women must wear the veil and chador and in response to large demonstrations by women, he modified his position and agreed that while the chador is not obligatory, modest dress is, including loose clothing and non-transparent stockings and scarves.18

With Islam's expansion into areas formerly part of the Byzantine and Sasanian empires, the scripture-legislate d social paradigm that had evolved in the early Medinan community came face to face with alien social structures and traditions deeply rooted in the conquered populations. Among the many cultural traditions assimilated and continued by Islam were the veiling and seclusion of women, at least among the urban upper and upper-middle classes. With these traditions' assumption into "the Islamic way of life," they of need helped to shape the normative interpretations of Qur'anic gender laws as formulated by the medireview (urbanized and acculturated) lawyer-theologians. In the latter's consensus-based prescriptive systems, the Prophet's wives were recognized as models for emulation (sources of Sunna). Thus, while the scholars provided information on the Prophet's wives in terms of, as well as for, an ideal of Muslim female morality, the Qur'anic directives addressed to the Prophet's consorts were naturally seen as applicable to all Muslim women.19

Semantically and legally, that is, regarding both the terms and also the parameters of its application, Islamic interpretation extended the concept of hijab. In scripturalist method, this was achieved in several ways. Firstly, the hijab was associated with two of the Qur'an's "clothing laws" imposed upon all Muslim females: the "mantle" verse of 33:59 and the "modesty" verse of 24:31. On the one hand, the semantic association of domestic segregation (hijab) with garments to be worn in public (jilbab, khimar) resulted in the use of the term hijab for concealing garments that women wore outside of their houses. This language use is fully documented in the medireview Hadith. However, unlike female garments such as jilbab, lihaf, milhafa, izar, dir' (traditional garments for the body), khimar, niqab, burqu', qina', miqna'a (traditional garments for the head and neck) and also a large number of other articles of clothing, the medireview meaning of hijab remained conceptual and generic. In their debates on which parts of the woman's body, if any, are not "awra" (literally, "genital," "pudendum") and many therefore be legally exposed to nonrelatives, the medireview scholars often contrastively paired woman's' awra with this generic hijab. This permitted the debate to remain conceptual rather than get bogged down in the specifics of articles of clothing whose meaning, in any case, was prone to changes both geographic/regional and also chronological. At present we know very little about the precise stages of the process by which the hijab in its multiple meanings was made obligatory for Muslim women at large, except to say that these occurred during the first centuries after the expansion of Islam beyond the borders of Arabia, and then mainly in the Islamicized societies still ruled by preexisting (Sasanian and Byzantine) social traditions.

With the rise of the Iraq-based Abbasid state in the mid-eighth century of the Western calendar, the lawyer-theologians of Islam grew into a religious establishment entrusted with the formulation of Islamic law and morality, and it was they who interpreted the Qur'anic rules on women's dress and space in increasingly absolute and categorical fashion, reflecting the real practices and cultural assumptions of their place and age. Classical legal compendia, medireview Hadith collections and Qur'anic exegesis are here mainly formulations of the system "as established" and not of its developmental stages, even though differences of opinion on the legal limits of the hijab garments survived, including among the doctrinal teachings of the four orthodox schools of law (madhahib). 20

Attacked by foreigners and indigenous secularists alike and defended by the many voices of conservatism, hijab has come to signify the sum total of traditional institutions governing women's role in Islamic society. Thus, in the ideological struggles surrounding the definition of Islam's nature and role in the modern world, the hijab has acquired the status of "cultural symbol."

Qasim Amin, the French-educated, pro-Western Egyptian journalist, lawyer, and politician in the last century wanted to bring Egyptian society from a state of "backwardness" into a state of "civilization" and modernity. To do so, he lashed out against the hijab, in its expanded sense, as the true reason for the ignorance, superstition, obesity, anemia, and premature aging of the Muslim woman of his time. He wanted the Muslim women to raise from the "backward" hijab into the desirable modernist ideal of women's right to an elementary education, supplemented by their ongoing contact with life outside of the home to provide experience of the "real world" and combat superstition. He understood the hijab as an amalgam of institutionalized restrictions on women that consisted of sexual segregation, domestic seclusion, and the face veil. He insisted as much on the woman's right to mobility outside the home as he did on the adaptation of shar'i Islamic garb, which would leave a woman's face and hands uncovered. Women's domestic seclusion and the face veil, then, were primary points in Amin's attack on what was wrong with the Egyptian social system of his time.21 Muhammad Abdu tried to restore the dignity to Muslim woman by way of educational and some legal reforms, the modernist blueprint of women's Islamic rights eventually also included the right to work, vote, and stand for election-that is, full participation in public life. He separated the forever-valid- as-stipulated laws of 'ibadat (religious observances) from the more time-specific mu'amalat (social transactions) in Qur'an and shari'a, which latter included the Hadith as one of its sources. Because modern Islamic societies differ from the seventh-century umma, time-specific laws are thus no longer literally applicable but need a fresh legal interpretation (ijtihad). What matters is to safeguard "the public good" (al-maslah al'-amma) in terms of Muslim communal morality and spirituality. 22

In the Veil and the Male Elite: A Feminist Interpretation of Women's Rights in Islam, the Moroccan sociologist Fatima Mernissi

attacks the age-old conservative focus on women's segregation as mere institutionalizatio n of authoritarianism, achieved by way of manipulation of sacred texts, "a structural characteristic of the practice of power in Muslim societies." In describing the feminist model of the Prophet's wives' rights and roles both domestic and also communal, Mernissi uses the methodology of "literal" interpretation of Qur'an and Hadith. In the selection and interpretations of traditions, she discredits some of textual items as unauthentic by the criteria of classical Hadith criticism. In Mernissi's reading of Qur'an and Hadith, Muhammad's wives were dynamic, influential, and enterprising members of the community, and fully involved in Muslim public affairs. He listened to their advice. In the city, they were leaders of women's protest movements, first for equal status as believers and thereafter regarding economic and sociopolitical rights, mainly in the areas of inheritance, participation in warfare and booty, and personal (marital) relations. Muhammad's vision of Islamic society was egalitarian, and he lived this ideal in his own household. Later the Prophet had to sacrifice his egalitarian vision for the sake of communal cohesiveness and the survival of the Islamic cause. To Mernissi, the seclusion of Muhammad's wives from public life (the hijab, Qur'an 33.53) is a symbol of Islam's retreat from the early principle of gender equality, as is the "mantel" (jilbab) verse of 33:59 which relinquished the principle of social responsibility, the individual sovereign will that internalizes control rather than place it within external barriers. Concerning A'isha's involvement in political affairs (the Battle of the Camel), Mernissi engages in classical Hadith criticism to prove the inauthenticity of the (presumably Prophetic) traditions "a people who entrust their command [or, affair, amr] to a woman will not thrive" because of historical problems relating to the date of its first transmission and also selfserving motives and a number of moral deficiencies recorded about its first transmitter, the Prophet's freedman Abu Bakra. Modernists in general disregard hadith items rather than question their authenticity by scrutinizing the transmitters' reliability.23 After describing the active participation of Muslim women in the battlefields as warriors and nurses to the wounded, Maulana Maudoodi24 says " This shows that the Islamic purdah is not a custom of ignorance which cannot be relaxed under any circumstances, on the other hand, it is a custom which can be relaxed as and when required in a moment of urgency. Not only is a woman allowed to uncover a part of her satr (coveredness) under necessity, there is no harm."

In the matter of hijab, the conscience of an honest, sincere Believer alone can be the true judge, as has been said by the Noble Prophet: "Ask for the verdict of your conscience and discard what pricks it."

Islam cannot be properly followed without knowledge. It is a rational law and to follow it rightly one needs to exercise reason and understanding at every step.25

REFERENCES

1. Cyril Glasse. The Concise Encyclopedia of Islam. Harper and Row Publishers, New York, N.Y., 1989, p. 156

2. Ibid, p. 413

3. Ibid, p. 421

4. Translation by Abdullah Yusuf Ali. The Holy Quran (Amana Corp., Brentwood, Maryland), 1989. Pp 873-874

5. Riffat Hassan. Women's Rights and Islam: From the I.C.P.D. to Beijing. Louisville, Kentucky, 1995. pp. 65-76

6. Translated and explained by Muhammad Asad. The Message of the Qur'an. Dar al-Andalus, Gibraltar. 1984. p.538

7. Bouthaina Shaaban.The Muted Voices of Women Interpreters. In

FAITH AND FREEDOM: Women's Human Rights in the Muslim World, Mahnaz Afkhami (Editor). I. B. Tauris Publishers, New York, 1995. p.68.

8. Nazira Zin al-Din, al-Sufur Wa'l-hijab (Beirut: Quzma Publications, 1928), p 37

9. Bouthaina Shaaban, op.cit. P.69

10. Nazira Zin al-Din, op.cit.pp. 191-2

11. Ibid, p.226

12. Bouthaina Shaaban, op. cit. p.72

13. Shaykh Mustafa al-Ghalayini, Islam ruh al-madaniyya (Islam:

The Spirit of Civilization) (Beirut: al-Maktabah al-Asriyya,

1960) P.253

14. Ibid, pp.255-56

15. Shaykh Muhammad al-Ghazali.: Sunna Between Fiqh and Hadith

(Cairo: Dar al-Shuruq, 1989, 7th edition, 1990)

16. Ibid, p.44

17. Abd al-Halim Abu Shiqa.: Tahrir al-mara' fi 'asr al-risalah

(Kuwait: Dar al-Qalam, 1990)

18. Jane I. Smith.:The Experience of Muslim Women:Consideration s

of Power and Authority. In The Islamic Impact. Haddad, Y.Y. (Editor), Syracuse University Press. 1984. Pp. 89-112

19. Barbara Freyer Stowasser.: Women in the Qur'an, Traditions, and Interpretation.Oxford University Press. 1994. P. 92

20. Ibid, p.93

21. Ibid, p.127

22. Ibid, p.132

23. Ibid, p.133

24. Syed Abu Ala Maudoodi. Purdah and the Status of Woman in Islam. Islamic Publications. Lahore, Pakistan. 1972. P.215

25. Ibid, p.203

Monday, March 26, 2007

Ideals and role models for women in Qur'an, Hadith and Sirah

Exhibitions portray ideals: all that is best in a person's work, a society, a period of artistic endeavour and so on. A talk at an exhibition should do the same, so I shall begin by putting forward the ideals of Islam concerning women, and their role models. I shall show how these ideals are set forth in the Qur'an, which Muslims consider to be the revealed word of God - Allah - in the Arabic language, and also refer to the Hadith and Sunnah, the reports of the sayings and the model practice of the Prophet Muhammad*. These two sources make up the basis for the Islamic law, Shari'ah, the body of legislation and moral guidance constructed by the Muslim scholars. Although the Qur'an is taken as unchallengeable, each Hadith is open to well-founded scholarly question as to its authenticity; and the interpretations given to the Qur'an and Hadith, which frequently result in differences of opinion, are open to still further questioning. The many different opinions expressed by the scholars give latitude to Muslims to choose between them to find acceptable guidelines. The Islamic law is not as monolithic and unchangeable as it might appear, although it does have a base of absolutes on which to stand.

This preamble is important with regard to women in Islam, because it has often been observed by Muslim scholars that the Islamic family law as practised in some Muslim countries bears little resemblance to the liberating and sympathetic treatment of women pioneered by the Prophet Muhammad himself (pbuh). Even Mawdudi, considered by some to be among the most conservative of modern Islamic revivalist commentators, Abul A'la Mawdudi, has criticisms to make of the why Indian Muslim law has been practised1. So it is important to distinguish between current, or even past practice, and the spirit of the law - the ideals as laid down by Allah in the Qur'an and exemplified by the Prophet Muhammad*. Most modern writers on Women in Islam are agreed that it is vital to go back to these original sources and reinterpret them in the context of the societies in which we all live now in order to clear up corruptions which have been incorporated into the laws, both from indigenous cultural sources and European colonialist efforts to, as they thought, `reform' the Shari'ah. So it is to these original sources, the Qur'an and Hadith, that I shall mainly refer.

The Qur'an has much to say both ABOUT women, and TO women. One Surah is called `Women', another is named after Maryam the mother of Jesus (pbuh). Women appear in many other parts. In stories of the prophets we have

- Hawwa (Eve) the wife of Adam, no longer the temptress who leads Adam to sin but a partner jointly responsible with him and jointly forgiven by Allah soon afterwards.

- There is the wife of Nuh (Noah) (pbuh) who betrays her husband and is held up along with the wife of Lot as an example of a disbeliever (66:10-11).

- There is the wife of Ibrahim, who laughs at the news the angel brings, of the baby she is to have in her old age;

- the wife of Pharaoh, who saves the infant Musa (Moses) (pbuh) and, along with Maryam, mother of Jesus, is one of the two female examples of the good believer held up in Surah 66:10 & 11.

- The wife of Aziz, who tried to seduce Yusuf (Joseph), is nevertheless treated with some sympathy, when she shows her friends how handsome he is and they all cut themselves with their knives because they are distracted by his beauty;

and there are more women besides.

It is noteworthy that the four women I have mentioned as examples are presented to both male and female Muslims to show how it is possible to be true believers in difficult circumstances, and disbelievers in favourable circumstances.

- The two good examples believed in spite of the attitudes of those close to them, Pharaoh's wife saving Moses from her husband's wicked command to kill all the Hebrew firstborn sons, and Maryam confronting accusations of immorality when she brought home her baby after the virgin birth.

- The two bad ones disbelieved in spite of being married to prophets of Allah. In neither case do these examples show the traditional picture of the `submissive' woman.

Then there are the contemporary women of the Prophet's household, his wives and daughters. One of his wives, Umm Salamah, complained to him that the Qur'an was addressed only to men, and then a long passage was revealed to the Prophet* addressed clearly to men and women in every line, which states clearly the equal responsibilities and rewards for Muslim men and women.

For Muslim men and women - for believing men and women, for devout men and women, for true men and women, for men and women who are patient and constant, for men and women who humble themselves, for men and women who give in charity, for men and women who fast (and deny themselves), for men and women who guard their chastity, and for men and women who engage much in God's praise - for them has God prepared forgiveness and great reward.

(Qur'an 33:35)

Aishah, his youngest wife, caused a scandal when she went out into the desert to look for a necklace she had lost there and got left behind by the caravan. She was rescued by a young man and came back with him and rumours spread that she had been dallying with him. This caused great pain to her and to the Prophet and it was a long time before they were relieved by another revelation (24:4), demanding that people making such accusations against chaste women must produce four eye witnesses to the act or suffer a flogging themselves and have their evidence rejected ever after.

There are passages specifically addressed to the wives of the Prophet as a group. For example:

O Consorts of the Prophet! Ye are not like any of the (other) women. If Ye do fear (Allah) be not too complaisant of speech, lest one in whose heart is a disease should be moved with desire, but speak Ye a speech (that is) just.

And stay quietly in your houses, and make not a dazzling display, like those of the former times of ignorance, and establish regular prayer, and give zakat (welfare due) and obey Allah and His Messenger. And Allah only wishes to remove all abomination from you, Ye members of the family, and to make you pure and spotless.

And recite what is rehearsed to you in your houses of the Signs of Allah and His Wisdom, for Allah is All-Subtle, All-Aware.

Qur'an 33:32-34

Other passages are addressed via the Prophet to his wives, daughters and the women of the believers.

Still others were revealed in answer to questions from ordinary women, like the one concerning the practice of divorce by abstinence within the marriage (zihar). A woman complained to the Prophet about this practice, which left the woman with no sexual satisfaction, but still not free to marry another husband and a verse was revealed condemning this practice.

Allah has indeed heard (and accepted) the statement of the woman who pleads with thee concerning her husband and carries her complaint (in prayer) to Allah...

Qur'an 58:1

Another passage was revealed in answer to a woman's complaint about the way her husband wanted to have intercourse with her (2:223).

So the Qur'an is a book which has a lot to say TO women and ABOUT women. What does it say? We have already seen that it does not condemn all women in the image of Eve as Christianity has been known to do; that it is often on the side of women who complain about injustice, in marriage, divorce and in false accusation. How does it view the creation of woman? Is she just a part of Adam and an afterthought? This is what it says, in the first Ayah (verse) of Surah an-Nisa - The Women:

O Mankind, be conscious of your duty to your Lord Who created you from a single soul, and from it created its mate (of the same kind) and from them twain has spread a multitude of men and women.

Qur'an 4:1

`A single soul' is neither male nor female, although it could be understood to mean Adam it is not necessarily so. In fact `soul' is feminine and `mate' is masculine! Not that I'm suggesting that women came first, because in other parts of the Qur'an the creation of Adam is described. But the gender relationship here is ambivalent. And the mate was created from the `soul' not the humble `rib'. No Muslim scholar could ever argue, after reading this, as some Christians have done, that women do not have a soul! They are made of the same soul as men. Their capacity for good and evil is identical with that of men. In 49:13, of the Qur'an we find that it is good deeds and awareness of Allah which make the believer, male or female, noble in the sight of Allah:

Indeed the noblest of you in the sight of Allah is the most pious.

and in 40:40:

Whoever does right, whether male or female, (all) such will enter the garden.

The works of male and female are of equal value and each will receive the due reward for what they do:

Never will I suffer to be lost the work of any one of you, male or female...

Qur'an 3:195

Whoever works righteousness, man or woman, and has faith, verily to him will We give a new life that is good and pure, and We will bestow on such their reward according to their actions.

Qur'an 16:97

The same duties are incumbent on men and women as regards their faith:

For Muslim men and women - for believing men and women, for devout men and women, for true men and women, for men and women who are patient and constant, for men and women who humble themselves, for men and women who give in charity, for men and women who fast (and deny themselves), for men and women who guard their chastity, and for men and women who engage much in God's praise - for them has God prepared forgiveness and great reward.

(Qur'an 33:35)

There are a few exceptions: women are given exemption from some duties,

- Fasting when they are pregnant or nursing or menstruating,

- Praying when menstruating or bleeding after childbirth, and

- The obligation to attend congregational prayers in the mosque on Fridays.

- They are not obliged to take part as soldiers in the defence of Islam, although they are not forbidden to do so.

But under normal circumstances they are allowed to do all the things that men do.

- Even when they are menstruating, on special days, like the two Id festivals, they are still allowed to come to the Id prayers, and menstruating women can take part in most of the actions of the Hajj pilgrimage.

But are women's duties in social life different and complementary as most scholars assert? Is their sole function to keep house and bear and rear children while the men do everything else? Does the fact that they suffer disruption to their health when they menstruate make them unsuitable for any job outside the house, and fit only to maintain a happy and peaceful home, as Mawdudi would have us believe? This is an argument that is grossly exaggerated by male scholars everywhere to justify all kinds of discrimination against women. Mawdudi would have us believe that women scarcely enjoy a few days' sanity in their lives, so disruptive are the effects of menstruation and childbearing. No doubt there is some truth in his description of such disruption, and allowances should be made by men, and other women for this, but this does not disqualify women from any task that men can do any more than it disqualifies them from creating happy and well-run homes.

Nor is there any basis in the Qur'an or Hadith for such an attitude. The Qur'an mentions menstruation in 2:222:

They ask thee concerning women's courses. Say: `They are a hurt and a pollution, so keep away from women in their courses, and do not approach them until they are clean. But when they have purified themselves, Ye may approach them as ordained for you by Allah.'

According to the interpreters of Islamic law, this means only that sexual intercourse is not allowed at such times, but any other form of intimacy is still permissible. To put it briefly, menstruation may be messy and painful but it is not a major disability.

Islamic law makes no demand that women should confine themselves to household duties. In fact the early Muslim women were found in all walks of life. The first wife of the Prophet, mother of all his surviving children, was a businesswoman who hired him as an employee, and proposed marriage to him through a third party; women traded in the marketplace, and the Khalifah Umar, not normally noted for his liberal attitude to women, appointed a woman, Shaff'a Bint Abdullah, to supervise the market. Other women, like Laila al-Ghifariah, took part in battles, carrying water and nursing the wounded, some, like Suffiah bint Abdul Muttalib even fought and killed the enemies to protect themselves and the Prophet* and like Umm Dhahhak bint Masoud were rewarded with booty in the same way as the men. Ibn Jarir and al-Tabari siad that women can be appointed to a judicial position to adjudicate in all matters, although Abu Hanifah excluded them from such weighty decisions as those involving the heavy hadd and qisas punishments, and other jurists said that women could not be judges at all. The Qur'an even speaks favourably of the Queen of Sheba and the way she consulted her advisors, who deferred to her good judgement on how to deal with the threat of invasion by the armies of Solomon. (Qur'an 27:32-35):

She (the Queen of Sheba) said, `O chiefs, advise me respecting my affair; I never decide an affair until you are in my presence.' They said, `We are possessors of strength and possessors of mighty prowess, and the command is Thine, so consider what thou wilt command.' She said,

`Surely the kings, when they enter a town, ruin it and make the noblest of its people to be low, and thus they do. And surely I am going to send them a present, and to see what (answer) the messengers bring back.'

Women have sometimes headed Islamic provinces, like Arwa bint Ahmad, who served as governor of Yemen under the Fatimid Khalifahs in the late fifth and early sixth century.

A much vaunted Hadith that the Prophet said, `A people who entrust power to a woman will never prosper', has been shown to be extremely unreliable on several counts. It is an isolated and uncorroborated one, and therefore not binding in Islamic law, and in addition there is reason to believe it may have been forged in the context of the battle which Aishah the Prophet's widow led against the fourth Khalifah Ali. In view of the examples set by women rulers in history, it is also clearly untenable and false.

To sum up, the qualifications of women for work of all kinds are not in doubt, despite some spurious ahadith to the contrary. Women can do work like men, but they DO NOT HAVE to do it to earn a living. They are allowed and encouraged to take the duties of marriage and motherhood seriously and are provided with the means to stay at home and do it properly.

The Muslim woman has always had the right to own and manage her own property, a right that women in this country only attained in the last 100 years. Marriage in Islam does not mean that the man takes over the woman's property, nor does she automatically have the right to all his property if he dies intestate. Both are still regarded as individual people with responsibilities to other members of their family - parents, brothers, sisters etc. and inheritance rights illustrate this. The husband has the duty to support and maintain the wife, as stated in the Qur'an, and this is held to be so even if she is rich in her own right. He has no right to expect her to support herself, let alone support his children or him. If she does contribute to the household income this is regarded as a charitable deed on her part.

Because of their greater financial responsibilities, some categories of male relations, according to the inheritance laws in the Qur'an, inherit twice the share of their female equivalents, but others, whose responsibilities are likely to be less, inherit the same share -mothers and fathers, for instance are each entitled to one sixth of the estate of their children, after bequests (up to one third of the estate) and payment of debts. (Qur'an 4:11):

For parents a sixth share of the inheritance to each if the deceased left children;

If no children, and the parents are the (only) heirs, the mother has a third; if the deceased left brothers (or sisters) the mother has a sixth...

Women are thus well provided for: their husbands support them, and they inherit from all their relations. They are allowed to engage in business or work at home or outside the house, so long as the family does not suffer, and the money they make is their own, with no calls on it from other people until their death.

Nor are women expected to do the housework. If they have not been used to doing it, the husband is obliged to provide domestic help within his means, and to make sure that the food gets to his wife and children already cooked. The Prophet* himself used to help with the domestic work, and mended his own shoes. Women are not even obliged in all cases to suckle their own children. If a divorcing couple mutually agree, they can send the baby to a wet-nurse and the husband must pay for the suckling. If the mother decides to keep the baby and suckle it herself, he must pay her for her trouble! This is laid down in the Qur'an itself, (2:233):

The mothers shall give suck to their offspring for two whole years, if the father desires to complete the term, but he shall bear the cost of their food and clothing on equitable terms...If they both decide on weaning, by mutual consent, and after due consultation, there is no blame on them. If Ye decide on a foster-mother for your offspring, there is no blame on you, provided Ye pay what Ye offered on equitable terms ...

What basis does all this leave for the male attitude that women are only fit for maternal and household duties?

Nevertheless the womanly state in marriage is given full respect in Islam, and so are the rights of children. No Muslim woman could feel ashamed to say she was only a housewife. She is the head of her household, although the husband has the final say in major decisions. According to a Hadith:

The ruler is a shepherd and is responsible for his subjects, a husband is a shepherd and is responsible for his family, a wife is a shepherd and is responsible for her household, and a servant is a shepherd who is responsible for his master's property.

Hadith: Bukhari

The wife must defer to her husband in respect for the fact that he maintains and protects her out of his means (Qur'an 4:34), but not if he tries to make her break the laws of Allah. Likewise children's obedience and respect for parents goes only to the limits set by Allah. If the parents try to make them disobey Allah, then it is their duty to disobey the parents. If the husband wilfully fails to maintain his wife, she has the right to divorce him in court.

Women are also entitled to respect as mothers: Allah says in the Qur'an (31:14):

And we have enjoined on man (to be good to his parents: in travail upon travail did his mother bear him...

The Prophet* said:

Paradise lies at the feet of mothers...

and in another Hadith the Prophet* told a man that his mother above all other people, even his father, was worthy of his highest respect and compassion.

In cases of divorce, the mother has first claim to custody of the young children, followed by other female members of her family, if she remarries or is unable to look after the children. The right reverts to the husband's family only after the children reach an age of greater independence, which varies according to the school of law, and then the wishes of the child must be taken into consideration, if the example of the Prophet* is to be followed. In a disputed case, he asked the child:

This is your father and this is your mother, so take whichever of them you wish by the hand.

Hadith: Abu Dawud, Nasa'i, Darimi

The boy went to his mother.

In another case a woman approached the Prophet telling him that her husband had embraced Islam while she had refused to do so, adding that her daughter was being deprived of mother's milk as her father was taking her away. The Prophet made the child sit between mother and father and said both of them should call her. The child would go to whoever she chose. The child responded to the mother. The Prophet prayed to Allah to guide the child and the child then chose the father, and hence Rafi (the father) took the child (Hadith: Abu Dawud)3

Yet in this country it is still a novelty to give the child such rights.

Although the Islamic marriage contract is a civil agreement between the two parties, not a sacrament like the Christian one, it is not just a relationship of material convenience. The words used to describe marriage in the Qur'an are poetic and beautiful:

And among His signs is this: that He created for you mates from among yourselves, that Ye may dwell in tranquillity with them, and He has put love and mercy between your hearts, verily in that are Signs for those who reflect.

Qur'an 30:21

They are your garments and Ye are their garments

Qur'an 2:187

Love, mercy, intimacy and mutual protection and modesty are the qualities expected of an Islamic marriage. Even in Paradise marriage remains as one of the great joys:

Verily the Companions of the Garden shall that day have joy in all that they do; they and their spouses will be in groves of (cool) shade reclining on thrones of (dignity); fruit will be there for them, they shall have whatever they call for; `Peace', a word (of salutation) from a Lord Most Merciful.

Qur'an 36:55-57

Husbands are expected to treat their wives kindly during marriage and even during and after divorce. Allah says in the Qur'an:

... Live with them on a footing of kindness and equity. If Ye take a dislike to them, it may be that Ye dislike a thing, and Allah brings about through it a great deal of good.

Qur'an 4:19

The Prophet* said:

The most perfect believers are the best in conduct and the best of you are those who are best to their wives.

(Hadith: Ibn Hanbal)

Married couples are urged in the Qur'an to deal with one another in a spirit of mutual consultation and agreement, even when contemplating divorce and the custody of children:

... If they both decide on weaning, by mutual consent, and after due consultation, there is no blame on them ...

Qur'an 2:233

How much more so, then, should this spirit predominate in the happy marriage!

Marriage is also intended by Allah to be fruitful. In the Qur'an He tells us:

... He has made for you pairs from among yourselves, and pairs among cattle; by this means does he multiply you...

Qur'an 42:11

Your wives are as a tilth for you ...

Qur'an 2:223

Yet contraception has never been forbidden in Islam, as the Prophet* gave permission for the withdrawal method, so long as the wife agrees. By analogy other methods of preventing conception are also allowed.

The practical aspects of marriage are covered by the marriage contract, in which the wife can specify conditions, and many Muslim women have taken advantage of this to take to themselves the right of divorce if, for example, the husband takes another wife (CARDS on Polygamy). It must include a marriage gift - sadaqah or mahr - to the wife from the husband, of an amount and nature agreed between them. Usually, according to custom and convenience - a practice later endorsed in the Shari'ah - a young inexperienced woman would be represented in the negotiations by a `marriage guardian' or wal_ who is there to see that her interests are served. This wal_ should be her father or grandfather, but it is possible for some older or more experienced women to appoint any person of their choice to act for them. When the Prophet* married the widow, Umm Salamah, her son acted as her wal_, and the Prophet* asked his permission to marry her. (Ibn Rushd) The wishes of close relations, in particular parents, must be taken into consideration, and their permission must be asked. According to some ahadith it is better to break off a marriage which displeases one's parents, as they are the gateway to Paradise.

Parents have a responsibility to help their children find spouses,

Umar Ibn al-Khattab and Anas reported God's Messenger* as saying that it is written in the Torah, `If anyone does not give his daughter in marriage when she reaches 12 and she commits sin, the guilt of that rests on him.'

Hadith: Baihaqi

and

Abu Sa'id and Ibn Abbas reported God's Messenger* as saying: `He who has a son born to him should give him a good name and a good education and marry him when he reaches puberty. If he does not marry him when he reaches puberty and he commits sin, its guilt rests only upon his father.

Hadith: Baihaqi

But parents have no right to force young women to marry against their will after they have reached marriagable age. There is much evidence in the Hadith to show that forced marriages are not legal and the wife has the right to have them annulled:

Ibn Abbas reported that a girl came to the Messenger of Allah, Muhammad* and she reported that her father had forced her to marry without her consent. The Messenger of Allah* gave her the choice ... (between accepting the marriage and invalidating it).

Hadith: Ibn Hanbal

In another version the girl said,

`Actually, I accept this marriage but I wanted to let women know that parents have no right (to force a husband on them).

Hadith: Ibn Majah

The Prophet* also advised that couples should see one another before getting married, so there is no Islamic basis for the custom of marrying young couples who have never set eyes on one another. If a woman does find that she cannot bear the man she is married to, even because she finds him ugly, Islamic law makes it possible for a court to give her a divorce from him. It is only necessary to prove that she hates him irrevocably - the court does not need to probe into the reasons for the hatred. The Prophet* granted divorces to at least two women in such circumstances. One of them, Jamila, the sister of the hypocrite Abdullah Ibn Ubayy, told the Prophet* about her objection to her husband Thabit Ibn Qais:

Messenger of Allah! Nothing can keep the two of us together. As I lifted my veil, I saw him coming, accompanied by some men. I could see that he was the blackest, the shortest and the ugliest of them all. By Allah! I do not dislike him for any blemish in his faith or his morals, it is his ugliness that I dislike. Had the fear of Allah not stood in my way, I must have spat on him when he came to me. ... I am afraid my desperation might drive my Islam closer to disbelief.

The Prophet asked her if she would return the garden Thabit had given her, and she agreed to do this and was given a divorce.4 Thabit did not do any better with his other wife, Habibah. And there are also examples of similar cases from the times of the first three Khalifahs.

Ideally speaking, women in Islam are treated like queens, indeed they are better protected than our British royal family is now! Not only are they are allowed to divorce their husbands, rather than live apart and unable to remarry, like Princess Diana, but they are also protected from scandal-mongers. No-one is allowed, without permission, to invade their privacy in their houses (24:27-28) not even their husbands when they return from a long journey. Men are not allowed to treat them with disrespect, to look at them more than once, or to touch them -even, some Hadith seem to show, to shake their hands - and if anyone spreads rumours about their chastity without the support of four eye witnesses to the act itself, they themselves are liable to punishment in this life and the hereafter (24:23)!

To make this demand for respect abundantly clear to the men, the wives of the Prophet are asked in the Qur'an to be modest in their appearance, and behaviour, to stay quietly in their houses and not make a great display of themselves as some well-known people were (and still are) prone to do; not to speak too pleasantly to men for fear of `those in whose hearts is a disease', and to be pious and virtuous and pure.

Ordinary Muslim women too are urged to lower their gaze and wrap themselves closely in their outer garments, letting their head-coverings fall over their neck opening, so that they may be recognised as respectable women and not molested. The Prophet's wives are also reported to have covered part of their faces with their cloaks when they were among strange men. Those who regard veiling as a form of exploitation should ask themselves which is more exploitative of women, the mini skirt or the veil?

Many Muslim women, from the Prophet's wives onwards, have aspired to the same degree of modesty and virtue as these passages enjoin and yet managed to participate actively in society by doing good deeds, working to help support their families, and/or pursuing their education. Women figured prominently among the earliest scholars of Islam. The Prophet's wife Aishah was one of the foremost transmitters of Hadiths and, like other wives and Companions of the Prophet was often surrounded by students wanting to learn from her: one of her pupils, Urwah Ibn az-Zubayr said:

I did not see a greater scholar than Aishah in the learning of the Qur'an, obligatory duties, lawful and unlawful matters, poetry and literature, Arab history and genealogy.

Abu Musa al-Ash'ar_ said:

Whenever we Companions of the Prophet* encountered any difficulty in the matter of any Hadith we referred it to Aishah and found that she had definite knowledge about it.

Hafiz ibn Hajar said:

... it is said that a quarter of the injunctions of the Shari'ah are narrated from her.

The Prophet* was keen to see that women were educated in Islam as well as the men and ordered the men to pass on what they had learned to their women:

Return home to your wives and children and stay with them. Teach them (what you have learned) and ask them to act upon it.

Hadith: Bukhari (CARD)

Muslim women have the right to have education from their husbands and if not, to go elsewhere to get it. An early Muslim scholar, of the Maliki school of law, named Ibn al-HÆjj, otherwise a strict critic of the over-liberal behaviour of the women in Cairo, wrote:

If a woman demands her right to religious education from her husband and brings the issue before a judge, she is justified in demanding this right because it is her right that either her husband should teach her or allow her to go elsewhere to acquire education. The judge must compel the husband to fulfil her demand in the same way that he would in the matter of her worldly rights, since her rights in matters of religion are most essential and important.

al-Mudhkal

Women can be educated by men. The Prophet sent Umar Ibn al-Khattab to teach the women of the Ansar:

It is reported by Umm `Atiyah thaat when the Messenger of Allah came to Madinah, he ordered the women of the Ansar (Muslims of Madinah) to gather in one house, and sent Umar Ibn al-Khattab to them (to convey the teachings of Islam). He saluted them while standing at at the door of the house and they returned his greeting. Then he said, `I am a messenger of the Messenger of Allah, sent especially to you.'

Hadith: Bukhari

And women taught men too, not only the wives of the Prophet but many others later were teachers of men, e.g. Aishah bt. Sa'id Ibn Abi Waqqas, who taught the first compiler of Hadith, Malik; and Sayyida Nafisa, granddaughter of al-Hasan, the Prophet's grandson, who taught Imam Shafi'i, and much later a woman taught Ibn al-Arabi, the famous Sufi thinker and greatly influenced his thought.

According to the Prophet*:

It is the duty of every Muslim (male or female) to seek knowledge.

Hadith: Bukhari?

Women's views were listened to, respected, and usually supported, by the Prophet* as we have seen. Another example is when the Prophet's pilgrimage to Makkah was stopped by the Makkans who made an agreement with him that he and the Muslims could return the following year. He told the people to shave their heads and offer their sacrifices where they were, but they did not obey, so he asked his wife Umm Salamah, and she advised him to lead them by doing so himself. He took her advice, and it worked. His successors, even the rather male chauvinist Khalifah Umar, did their best to follow his example in this. Umar, trying to regulate the exorbitant demands for mahr marriage gifts that women were making had to retreat after a woman stood up and disputed with him, quoting the Qur'an to support her case:

Umar forbade the people from paying excessive dowries and addressed them, saying: `Don't fix dowries for women over 40 ounces. If ever that is exceeded I shall deposit the excess amount in the public treasury.' As he came down from the minbar (platform), a flat-nosed lady stood up from among the women audience and said:

'It is not within your right.' Umar asked: `Why should this not be of my right?' She replied, `Because Allah has proclaimed, "Even if you had given one of them (wives) a whole treasure for dower, take not the least bit back. Would you take it by false claim and manifest sin?' (Qur'an 4:20)

When he heard this, Umar said: `The woman is right, and the man (Umar) is wrong. It seems that all people have deeper wisdom and insight than Umar.' Then he returned to the minbar and said, `O people! I had restricted the giving of more than four hundred dirhams in dower. Whosoever of you wishes to give in dower as much as he likes and finds satisfaction in so doing, may do so.'

Hadith: Ibn al-Jawzi

Umar also used to seek the counsel of Shaffa the market inspector, pay due regard to her and hold her in high esteem. (Ibn Hajar al-Isabah quoted by Hasan Turabi)

So, to conclude, these are the ideals to which Muslim women can aspire and frequently have done in the past. In a truly Islamic society, they are guaranteed

- personal respect,

- respectable married status,

- legitimacy and maintenance for their children,

- the right to negotiate marriage terms of their choice,

- to refuse any marriage that does not please them,

- the right to obtain divorce from their husbands, even on the grounds that they can't stand them (Mawdudi),

- custody of their children after divorce,

- independent property of their own,

- the right and duty to obtain education,

- the right to work if they need or want it,

- equality of reward for equal deeds,

- the right to participate fully in public life and have their voices heard by those in power,

and much more besides. What other religion, political theory, or philosophy has offered such a comprehensive package???

Womens Rights In Islam

The right and duty to obtain education.

The right to have their own independent property.

The right to work to earn money if they need it or want it.

Equality of reward for equal deeds.

The right to participate fully in public life and have their voices heard by those in power.

The right to provisions from the husband for all her needs and more.

The right to negotiate marriage terms of her choice.

The right to obtain divorce from her husband, even on the grounds that she simply can't stand

him.

The right to keep all her own money (she is not responsible to maintain any relations).

The right to get sexual satisfaction from her husband